Abstract

Introduction:

Biliary atresia (BA) is a cholangodestrutive disease of the biliary tree that presents as pathologic jaundice. It occurs in 1 in 10,000 to 15,000 births in the United States. BA is the most common cause of end-stage liver disease and liver transplantation in children. Clinical manifestations include clay colored or alcoholic stools, impaired hematopoiesis, prolonged coagulation, and hepatosplenomegaly. Etiologies of biliary atresia include infectious, congenital, metabolic, acquired, autoimmune, and seasonal. Patients with BA should receive operative management within the first 60 days of life.

Case Report:

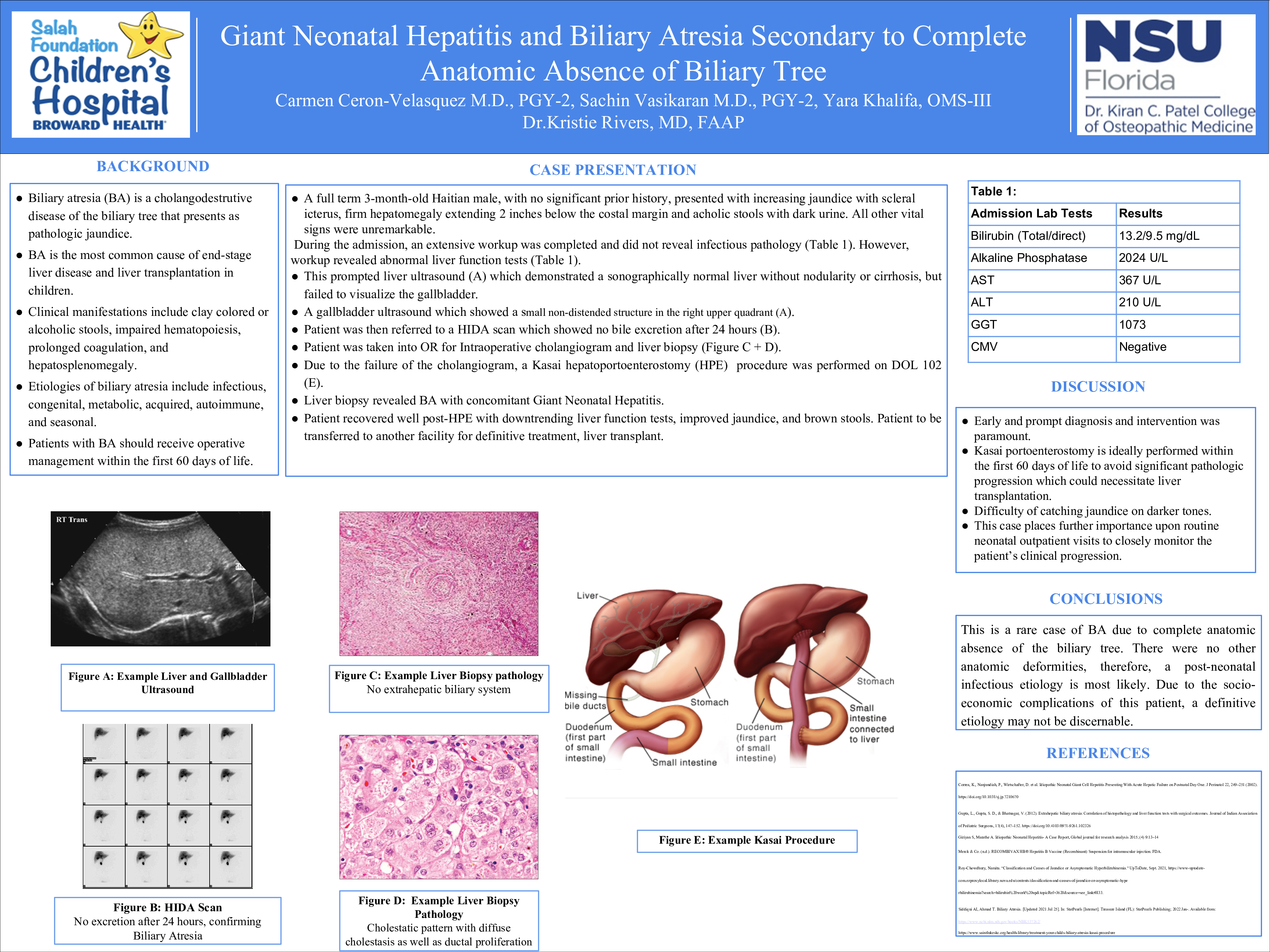

The patient is a full term 3-month-old Haitian male, with prior medical history notable for abnormal TFTs on newborn screen, who presented to his primary care physician’s office for a well child check up after being lost to follow up. No prior surgical history and no medications. Parental concerns during the visit included increasing yellowing of the eyes and skin, as well as pale appearing stools. On exam, the patient was jaundiced with scleral icterus, had firm hepatomegaly extending 2 inches below the costal margin. In addition, he was noted to be passing acholic stools with dark urine. Laboratory testing demonstrated elevations in bilirubin (total 13.2 mg/dL, direct 9.5 mg/dL), alkaline phosphatase (2024 U/L), AST (367U/L), and ALT (210U/L). He was immediately referred to our institution for a multidisciplinary evaluation. Infectious disease work up including cytomegalovirus, was otherwise negative. He underwent a liver ultrasound that demonstrated a sonographically normal liver without nodularity or cirrhosis, but failed to visualize the gallbladder. Gallbladder ultrasound revealed a small non-distended structure in the RUQ and a HIDA scan did not excrete after 24 hours. As a result, the patient underwent liver biopsy and intraoperative cholangiogram for suspected biliary atresia. The latter was unsuccessful since there was no extrahepatic biliary system. The biopsy demonstrated a cholestatic pattern with diffuse cholestasis as well as ductal proliferation. These findings were interpreted as consistent with biliary atresia, and thus the surgical team proceeded with the Kasai hepatoportoenterostomy (HPE) Of note, the patient underwent HPE on DOL 102. The patient recovered well postoperatively without significant complication. The final pathology confirmed biliary atresia with suggestive concomitant neonatal giant cell hepatitis. The patient continued to do well, with downtrending liver enzymes and bilirubin. No more scleral icterus, jaundice or acholic stools. However, since the patient was not diagnosed at an early stage, evaluation for liver transplant was recommended and therefore transfer to a pediatric transplant center was made.

Discussion:

This case highlights several important points. Due to the age of the patient, prompt diagnosis and intervention was paramount. Kasai portoenterostomy is ideally performed within the first 60